Vuaclub được rất nhiều người chơi lựa chọn nhờ mang đến nhiều tiện ích, khuyến mãi hấp dẫn và trò chơi đa dạng. Vậy bạn đã biết cách truy cập và tải cổng game này về thiết bị để trải nghiệm hay chưa? Nơi đây có những tựa game hot nào? Cách thức trở thành thành viên của Vua club ra sao? Nếu chưa anh em cùng sieuthisimthe.com.vn theo dõi nội dung và cập nhật link tải mới nhất 2024 cho mình nhé.

Link tải game mới nhất 2024

Dưới đây là link tải Vuaclub chính xác nhất, không bị chặn:

- Link tải game Vua club trên PC: https://sieuthisimthe.com.vn/

- Tải game Vua club cho Android/APK: https://sieuthisimthe.com.vn/

- Tải game vua club cho IOS: https://sieuthisimthe.com.vn/

Để có thể tìm được địa chỉ chính xác của cổng game người chơi cần phải thường xuyên cập nhật link mới mỗi ngày. Điều này cũng là do nhà mạng tại Việt Nam chặn các địa chỉ cá cược trực tuyến hoạt động cho nên cổng game chúng tôi cũng đang gặp tình trạng này.

Đội ngũ admin của cổng game đang nỗ lực khắc phục bằng cách liên tục cập nhật link tải mới nhất đến với người chơi. Với cách làm này người chơi có thể nhanh chóng truy cập mỗi ngày đồng thời cổng game cũng cải thiện thêm về hệ thống. Người chơi từ đó cũng có được trải nghiệm tốt hơn. Link vào trang chủ chính thất mới nhất dưới đây: sieuthisimthe.com.vn.

Giới thiệu về cổng game Vuaclub

Vuaclub hiện đang được rất nhiều cược thủ quan tâm bởi chất lượng các trò chơi cực kỳ đa dạng và chất lượng. Cổng game này được xây dựng tại Trung Quốc và chỉ mới xuất hiện tại Việt Nam vào đầu năm 2023 nhưng đã nhanh chóng nổi tiếng và được nhiều người lựa chọn. Mặc dù chỉ mới là tân binh trong làng cá cược trực tuyến thế nhưng cổng game lại nhanh chóng nhận được sự công nhận từ PAGCOR và cũng được tổ chức này cấp giấy phép kinh doanh hợp pháp.

Với sự đầu tư lớn về mọi mặt kết hợp với sự hậu thuẫn từ ông lớn trong ngành cá cược tại Trung Quốc cho nên sân chơi Vua Club phiên bản mới đã nhanh chóng có được chỗ đứng top đầu trên thị trường. Chỉ tính thời gian hoạt động tại Việt Nam, số thành viên truy cập mỗi ngày đã lên tới con số triệu người.

| Giao diện trang chủ | Giao diện đẹp mắt, âm thanh sống động |

| Tải app | Link tải chất lượng, thao tác đơn giản |

| Giao dịch nạp, rút tiền | Thời gian nhanh chóng, đơn giản |

| Khuyến mãi | X6 hũ mỗi ngày với tiền thưởng lớn |

| Kho tàng game cá cược | Game cá cược đa dạng, tiền thưởng lớn |

Đánh giá về cổng game số 1 hiện nay

Để có được vị trí số 1 trong danh sách những cổng game uy tín nhất hiện nay Vuaclub đã không ngừng đầu tư để có hệ thống đẳng cấp. Anh em hãy cùng tìm hiểu những đánh giá chi tiết về cổng game này từ những người chơi trước đó nhé:

Ưu điểm của cổng game

Với số lượng thành viên đông đảo như hiện nay, Vua clup đã chứng minh được chất lượng của mình. Một số ưu điểm được người chơi đánh giá cao sau khi tham gia cá cược tại cổng game này có thể kể đến như:

- Nhà phát hành đã rất chú trọng đến việc xây dựng hình ảnh, âm thanh cực kỳ sống động và đẹp mắt. Màu sắc được thiết kế hài hòa và các chuyên mục được sắp xếp khoa học giúp người chơi dễ dàng thao tác.

- Cổng game cung cấp khá nhiều phương thức thanh toán, các giao dịch đều có thao tác đơn giản, tốc độ hoàn thành nhanh chóng để người chơi không phải chờ đợi quá lâu.

- Cổng game cũng cam kết bảo mật thông tin của người chơi an toàn 100%, không có chuyện thông tin bị rò rỉ hay bị hacker đánh cắp tài khoản tại đây.

- Người chơi còn có nhiều cơ hội nhận được các ưu đãi hấp dẫn, có giá trị cao, từ đó gia tăng tiền vốn nhanh chóng hơn.

- Kho tàng game cũng cực kỳ đa dạng với nhiều thể loại cá cược khác nhau, các trò chơi đều có thiết kế hình ảnh đẹp mắt, luật chơi rõ ràng và tỷ lệ trả thưởng hấp dẫn để anh em cược thủ trải nghiệm.

Một số nhược điểm còn tồn tại

Mặc dù có rất nhiều ưu điểm được người chơi đánh giá cao nhưng Vuaclub vẫn có một số điểm còn hạn chế cần được khắc phục như:

- Link dẫn vào cổng game vẫn thường xuyên bị chặn do chính sách từ các nhà mạng nên người chơi mới thường khá lúng túng trong việc tìm đường dẫn mới để truy cập.

- Vào 1 số thời gian cao điểm hệ thống vẫn còn tình trạng hơi lag một chút với những dòng máy đời cũ, cấu hình thấp.

Các trò chơi nổi bật tại Vuaclub

Như đã giới thiệu ở phần trên, một trong những ưu điểm nổi bật của cổng game này chính là xây dựng được 1 kho tàng game cá cược đa dạng. Một số thể loại anh em có thể trải nghiệm tại cổng game này bao gồm:

Slots game

Vua club có nguồn tài chính khá hùng hậu vì thế các quỹ jackpot của slots game có tiền thưởng rất lớn. Hiện tại cổng game này cung cấp rất nhiều trò chơi hấp dẫn với nhiều chủ đề khác nhau. Mỗi trò chơi đều có những nét đặc trưng riêng với quỹ thưởng lên tới hàng trăm triệu đồng. Với thiết kế hình ảnh đẹp mắt, kết hợp âm thanh sống động sẽ khiến anh em hứng thú để tìm kiếm cơ hội jackpot cho mình. Một số trò chơi tạ slots game bao gồm:

- Hades

- Odin

- Wild Pops

- Loony Blox

- Gonzo’s Quest

- Foriune Miner

- Aztec

- Gear

- One Piece

- Bắn cá

- Pirates

- Zeus

- Berry Burst Max

- tdtc

Tiến lên miền nam

Tiến lên miền Nam là trò chơi game bài quen thuộc với dân chơi tại Việt Nam vì thế trò chơi này có số lượng thành viên cực đông. Cổng game đang cung cấp khá nhiều bàn cược với nhiều mức cược khác nhau để anh em có thể trải nghiệm. Sẽ có 2 phiên bản cho bạn lựa chọn là chơi đối kháng với những người chơi khác tại cổng game hoặc chơi solo với máy chủ.

Tài xỉu MD5

Đây là trò chơi hàng đầu tại đây bởi ngay khi bạn vừa truy cập giao diện bàn cược tài xỉu sẽ xuất hiện ngay để bạn có thể tham gia mà không phải chọn chuyên mục trò chơi nào. Cổng game này có cách chơi đơn giản, bạn chỉ cần tính toán để xem số xúc xắc nằm trong khoảng điểm của cửa Tài hay cửa Xỉu và đặt cược.

Bắn cá

Bắn cá chắc không còn là trò chơi xa lạ gì với nhiều người bởi đây là trò chơi phổ biến ở hầu hết các khu vui chơi hiện nay. Với sự đầu tư tỉ mỉ về hình ảnh, âm thanh Vua club đã tạo nên 1 đại dương đầy màu sắc với nhiều sinh vật biển khác nhau. Nhiệm vụ của người chơi chỉ cần sử dụng vũ khí để tiêu diệt các sinh vật biển và mang về tiền thưởng cho mình.

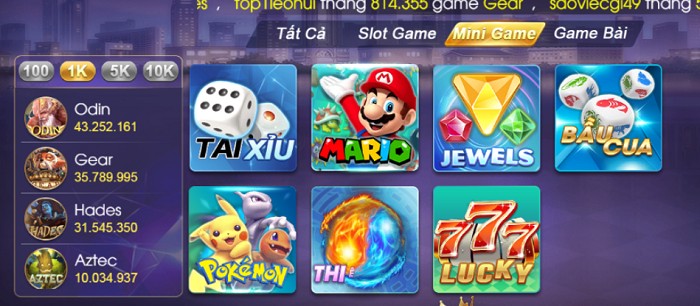

Mini game

Đối với những cược thủ không có nhiều thời gian để tham gia những trò chơi kéo dài thì mini game chính là sự lựa chọn tuyệt vời. Nắm bắt được nhu cầu này của cược thủ Vua club đã tạo một chuyên mục với rất nhiều trò chơi hấp dẫn. Các trò chơi có thời gian mỗi ván rất nhanh, cách chơi đơn giản nhưng tiền thưởng lại rất hậu hình. Anh em có thể tham gia 1 số trò chơi như:

- Tài xỉu

- Mario

- Bầu cua

- Thiên Địa

- Lucky

- Pokemon

- Jewels

Game bài

Nếu bạn là một cược thủ đam mê với những trò chơi đối kháng thì mục game bài rất thích hợp cho bạn. Cổng game đang cung cấp nhiều tựa game quen thuộc với dân chơi châu Á. Các trò chơi đều có luật chơi đơn giản, có nhiều mức cược để người chơi đặt cược theo khả năng tài chính của mình. Điểm đặc biệt tại đây chính là ngoài những trò chơi đối kháng thì cổng game còn có những trò chơi solo người chơi sẽ chơi với máy chủ để không có nhiều áp lực. Các trò chơi game bài được cung cấp bao gồm:

- Tiến lên miền Nam Solo

- Xóc xóc

- Sâm Solo

- Poker

- Tiến lên miền Nam 4 người

Hướng dẫn tải app Vuaclub chơi game tiện lợi

Vuaclub hiện đang rất được nhiều người chơi ưa chuộng và số lượng thành viên đang ngày càng tăng lên. Để đáp ứng được hết mọi nhu cầu của các thành viên cổng game này đã xây dựng các ứng dụng app trên thiết bị để người chơi có thể cá cược mọi lúc, mọi nơi.

Cách tải app cho Android

Các dòng điện thoại Android khá phổ biến trên thị trường cho nên nhu cầu người tải app Vuaclub cũng rất lớn. Các bước thực hiện tải ứng dụng app sẽ diễn ra như sau:

- Bước 1: Hiện tại cổng game này đang cung cấp link tải riêng biệt với giao diện trang chủ nên bạn cần cập nhật link tải trước khi tải app.

- Bước 2: Ở giao diện tải app hãy nhấn chọn mục “Tải bản cài đặt”, lúc này hệ thống sẽ điều hướng sang CHPlay.

- Bước 3: Bạn sẽ thấy có 1 ứng dụng khác xuất hiện, hãy nhấn tải như bình thường và chờ cho quá trình tải diễn ra thành công.

- Bước 4: Cuối cùng hãy mở ứng dụng vừa tải, đợi ứng dụng load và Update 100% thì giao diện trang chủ của Vuaclub sẽ xuất hiện.

Cách tải app cho IOS

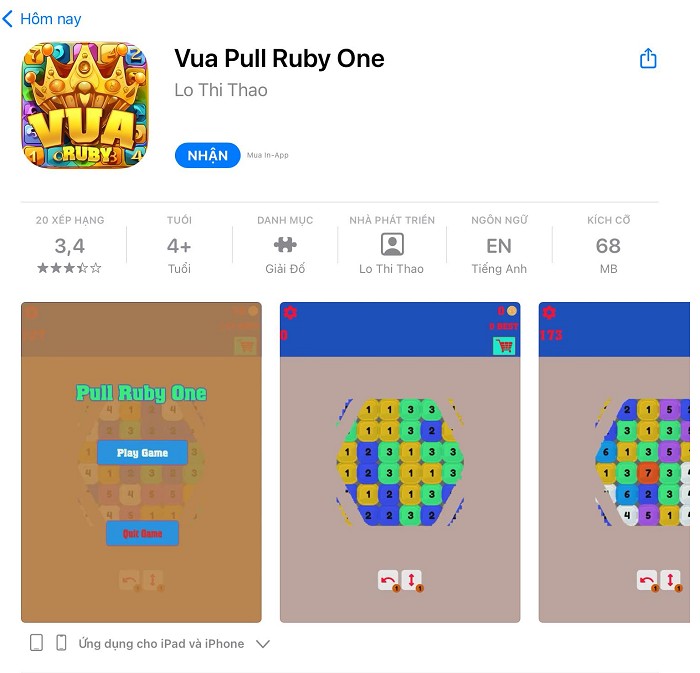

Đối với các dòng máy của IOS sẽ có phiên bản tải khác biệt so với các dòng máy sử dụng chung hệ điều hành Android. Cụ thể tải app cho IOS diễn ra như sau:

- Bước 1: Trước tiên bạn hãy tìm link tải app Vuaclub chất lượng và uy tín do cổng game cung cấp.

- Bước 2: Sau đó hãy nhấn vào mục “Tải bản cài đặt” để tiến hành tải app về điện thoại.

- Bước 3: Lúc này giao diện sẽ điều hướng sang Appstore và xuất hiện 1 ứng dụng mới là Vua Pull Ruby One, đây chính là ứng dụng do cổng game cung cấp để tránh bị IOS quét bảo mật.

- Bước 4: Bạn hãy nhấn tải app về như bình thường và đăng ký tài khoản sau đó đăng nhập, giao diện cổng game sẽ xuất hiện nhé.

Cách tải app cho PC

Ngoài việc chơi cá cược trên điện thoại nhiều người còn rất thích chơi trên máy tính như với phiên bản điện thoại để không mất thời gian tìm link truy cập. Với PC các bước tải app Vuaclub APK như sau:

- Bước 1: Trước tiên bạn cần chọn 1 phần mềm giả lập Androi phù hợp với dung lượng máy tính của bạn và tải về máy. Sau đó hãy giải nén file và cài đặt giả lập cho PC.

- Bước 2: Tiếp theo anh em cần khởi động phần mềm giả lập và thoát ra màn hình chính của máy tính, mở trình duyệt web và nhấn vào link tải app ở mục “Tải bản cài đặt”.

- Bước 3: Sau khi xuất hiện file tải của Vua.Club APK bạn hãy nhấn Đồng ý để app được đồng bộ với phần mềm giả lập trên máy tính của bạn.

- Bước 4: Bây giờ hãy quay lại màn hình chính của máy tính bạn sẽ thấy biểu tượng app Vuaclub đã xuất hiện, hãy nhấn vào biểu tượng ứng dụng sẽ tự động được cài đặt trên giả lập Android. Bạn hãy chờ hệ thống load thành công là đã vào được trang chủ của cổng game để tham gia cá cược rồi đấy.

Các khuyến mãi nổi bật tại Vuaclub

Hiện tại Vua club đang cung cấp một số chương trình khuyến mãi nổi bật dành riêng cho 2 thể loại cá cược là tài xỉu và nổ hũ. Cụ thể các chương trình ưu đãi như sau:

Khuyến mãi dành cho tài xỉu

Chương trình này diễn ra mỗi ngày dành cho những thành viên tham gia chơi tài xỉu tại Vua69 và mỗi ngày sẽ có tối đa là 7 phượng để người chơi nhận thưởng. Người chơi khi có dây thắng hoặc dây thua dài nhất sẽ được tính trong phiên Phượng Hoàng.

- Người có từ 15 dây thắng/thua (thắng hoặc thua liên tiếp 15 trận) sẽ có giải Phượng Hoàng với tiền thưởng từ 1.234.567 – 7.654.321 ngẫu nhiên từ hệ thống.

- Người có dây thắng/thua trong top 1 sẽ được nhận thưởng 500.000

- Người sở hữu dây thắng/thua trong top 2 sẽ được nhận thưởng 200.000

- Người nhận được dây thắng/thua trong top 3 sẽ được nhận thưởng 100.000

- Người chơi từ top 4-10 sẽ nhận được tiền thưởng là 50.000

- Người chơi trong top 11-50 sẽ nhận được thưởng là 20.000

- Người chơi thuộc top 51-100 sẽ có tiền thưởng là 10.000

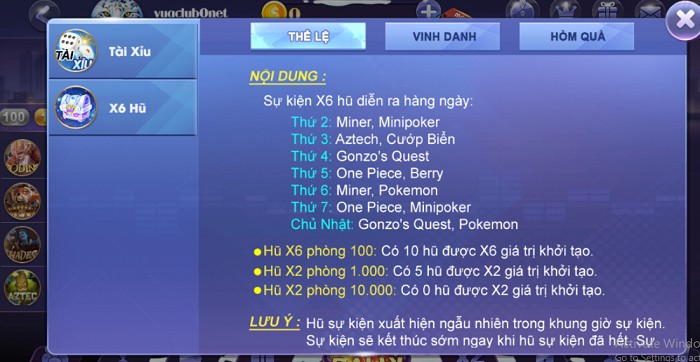

Khuyến mãi X6 hũ

Sự kiện X6 hũ sẽ diễn ra hàng ngày dành cho người chơi tại Vua club khi tham gia các trò chơi được quy định theo các ngày trong tuần. Cụ thể đó là:

- Thứ 2: dành cho Miner và Mini Poker

- Thứ 3: dành cho Cướp biển và Aztech

- Thứ 4: dành cho Gonzo’s Quest

- Thứ 5: dành cho Berry và One Piece

- Thứ 6: dành cho Miner và Pokemon

- Thứ 7: dành cho One Piece và Minipoker

- Chủ nhật: dành cho Gonzo’s Quest

Người chơi sẽ nhận được X6 giá trị khởi tạo bạn đầu khi có 10 hũ thuộc phòng 100. Còn nếu bạn ở phòng 1.000 sẽ được X2 khi có 5 hũ, còn nếu ở phòng 10.000 bạn sẽ tự động được X2 mà không có hũ nào. Chương trình này sẽ không có khung giờ cố định và hệ thống sẽ đóng chương trình khi các giải thưởng đã có chủ hoặc hết thời gian theo quy định.

Các kênh liên hệ Vuaclub nhanh nhất

Để hỗ trợ cho các thành viên tham gia cá cược về các vấn đề kỹ thuật hay hướng dẫn, cung cấp thông tin về thao tác trên hệ thống vuaclub đã cung cấp một số phương thức liên hệ thông qua Telegram và hotline. Đây là hai phương thức phổ biến và an toàn để người chơi vừa có thể trao đổi khi cần thiết và hạn chế được tình trạng thông tin bị rò rỉ cho bên thứ 3.

Các chuyên viên hỗ trợ đã được đào tạo bài bản đảm bảo hỗ trợ nhanh chóng, 24/7 cho người chơi. Thái độ tư vấn cũng rất nhiệt tình, niềm nở giúp cược thủ không cảm thấy khó chịu mỗi khi cần giúp đỡ, tư vấn.

Câu hỏi thường gặp khi chơi tại Vuaclub

Ngoài những thông tin nêu trên bạn còn có thể tìm hiểu về cổng game Vuaclub thông qua một số nội dung sau về các thắc mắc mà các chuyên gia đã tổng hợp, giải đáp tận tình, chi tiết như sau:

Vuaclub có uy tín hay không?

Như đã giới thiệu ở trên Vua club là cổng game số 1 tại Việt Nam và đã được chứng nhận chất lượng cũng như cấp giấy phép kinh doanh hợp pháp. Điều này còn được chứng minh từ số lượng thành viên tham gia mỗi ngày lên tới hàng triệu người nữa đấy.

Vuaclub lừa đảo có đúng không?

Các thông tin tố cáo Vuaclub lừa đảo là hoàn toàn sai sự thật. Đó là do các đối thủ cạnh tranh tung tin đồn để hạ thấp uy tín của cổng game. Ngoài ra có 1 số người chơi chưa nắm rõ quy định của hệ thống khiến việc tham gia cá cược có phần khó khăn nên hiểu nhầm chính sách của chúng tôi không rõ ràng.

Quên tài khoản đăng nhập phải làm sao?

Nếu chẳng may bạn quên tài khoản đăng nhập của mình thì có thể nhận vào mục Quên mật khẩu ở dưới khung điền thông tin để thay đổi thông tin. Hoặc anh em hãy liên hệ cho bộ phận CSKH của cổng game để được hỗ trợ nhanh chóng nhé.

Cách nhận Giftcode như thế nào?

Để có thể nhận được Giftcode từ Vua club bạn cần theo dõi các sự kiện mà cổng game này tổ chức ở trang chủ. Ngoài ra bạn còn phải theo dõi tài khoản Facebook của cổng game bởi các admin thường tổ chức nhiều sự kiện hay để thu hút người chơi. Sau khi đã thực hiện xong các yêu cầu bạn hãy gửi thông tin cho đội ngũ admin kiểm duyệt để nhận Giftcode. Cuối cùng hãy vào mục Giftcode ở trang chủ và điền mã số để lấy tiền thưởng nhé.

Có thể đăng ký được bao nhiêu tài khoản Vuaclub?

Theo quy định mỗi người chơi chỉ được đăng ký 1 tài khoản duy nhất để hoạt động tại cổng game. Nếu hệ thống quét thông tin phát hiện người chơi sử dụng từ 2 tài khoản trở lên thì toàn bộ tài khoản sẽ lập tức bị khóa vĩnh viễn dù đã sử dụng hay chưa?

Trên đây là toàn bộ thông tin cũng như hướng dẫn tải Vuaclub với link tải mới nhất dành cho anh em. Hi vọng nội dung bài viết tại sieuthisimthe.com.vn sẽ giúp bạn nhanh chóng truy cập vào tham gia trải nghiệm các trò chơi tại đây.